A look at Boris Johnson’s eight years as Mayor of London show some early warnings for the Labour Party ahead of the next general election.

The first is simply that the Labour Party has a terrible habit of underestimating Boris Johnson as a politician. The exception to this was in 2008 when Ken Livingstone saw through the bluster and identified that he was going to be his toughest opponent yet.

Ken’s former chief of staff (who also went on to run Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership campaign) quickly identified underestimating Johnson as a strategic error in a lengthy piece on campaigning against Johnson published just ahead of his selection victory. The piece clearly argues that for Labour to win, it cannot simply use negative attack lines against the new Prime Minister – it must set out its own positive dividing lines. This is something the Party may struggle to do. Part of Labour’s issue is that collectively it can too often react to the image Johnson projects rather than the substance of what he is saying, or indeed what he is doing.

The current Labour leadership likes to play to its base. One can therefore expect criticism of his background, his education, his bluster. However, this would be an error when facing Johnson as it would simply let him off the hook. The new PM has cultivated these attack lines for his opponents, daring them to attack him for his appearance rather than his actions, gambling that attacks on these lines only galvanise his support. When Labour does focus on his actions, it can often miss the target – in part because it is too focused on attacking the failures it links to his personality. Through this election process, London commentators have been quick to bring up the ‘Boris bus’ (and the cost to the taxpayer), the failed bid to develop the Thames Estuary Airport (and the cost to the taxpayer) and everyone’s favourite, the Garden Bridge (and the cost to the taxpayer).

There is one key error here. For every voter who is disgusted by the largesse, there will be another who applauds him for giving ideas a go and thinking big. We are bound to see some more examples of ‘grands projets’ in the early months of a Johnson administration and we are likely to see similar divided reactions. But for Johnson, divided reactions are OK – he knows how to use them.

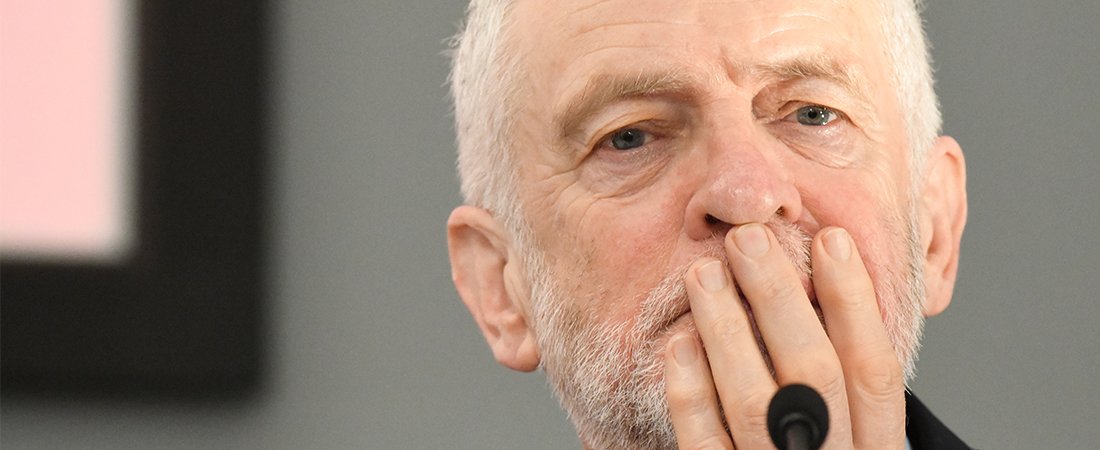

The focus on ‘Boris the Man’, as opposed to ‘Boris the Mayor’, suits Johnson well as he is an expert in the former. But he is by no means an expert in policy. This was quite evident through the under-viewed Mayor’s Question Time, where the London Assembly scrutinise the Mayor’s activities. There is a good, recent, article by Tom Copley, a Labour Assembly Member, which looks back at the lessons learned scrutinising the Mayor for his grasp of policy, and not allowing his brand to distract you. There are some wise words for Jeremy Corbyn contained within it – but whether he applies them or sticks with the current grandstanding at PMQs remains to be seen.

The final negative lesson for Labour is that, while Johnson is rarely interested in mastering the detail of a brief, he belatedly has learnt how to surround himself with people that enable him to do what he does best. It is well-documented that Boris did not really plan for a transition into City Hall. The previous blueprint, set by Ken Livingstone, was a hands-on Mayor focused on using the levers of power to shape the capital. Johnson had neither that long sweep of policy knowledge or a particularly strong vision for how to use London government to shape the capital. His early set of advisors did not quite make the grade (losing their posts for, among other things, lying on their CVs, racist comments or fiddling their expenses to cover up an extramarital affair).

It was only after the late, great, Sir Simon Milton was persuaded to focus more on London – becoming both Chief of Staff as well as Deputy Mayor for Planning – that City Hall began to show any form of direction. Following his untimely passing, there were rapid moves to bring in additional, experience ballast to avoid the chaos of the Mayor’s former appointments.

The biggest appointment was Sir Edward Lister, moving from 30 years leading Wandsworth Council to take over Sir Simon’s duties. The talented Rick Blakeway became Deputy Mayor for Housing, and then Daniel Moylan, a Councillor from the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC), who had begun to exert his influence over Transport for London as its Deputy Chairman began to front several key projects.

Given two of these three are now part of Boris Johnson’s No 10 team – with Sir Edward playing a Chief of Staff role and Daniel thought to be being brought on to play a role in Brexit – it is worth focusing on them.

When Sir Edward joined City Hall, he didn’t really have a significant profile. But his role in running Boris’ mayoralty was huge. In effect, he took 90-95% of decisions in City Hall with only the top issues being referred up to Boris for decision on either tone or strategic direction. He is a man used to making things work. Quite whether he will be able to exert his famous ‘Steady Eddie’ grip over the court of Johnson in Downing Street remains to be seen.

Daniel Moylan is a very different character, but no less capable. A common thread throughout his political career is the purity of an argument – whether it is removing street clutter, arguing for the Thames Estuary Airport, or pushing for Brexit – Daniel always exhibits a grip of facts and an intellectual flourish to intimidate opponents. He has never been shy of being provocative. Those keen to stop a ‘no deal’ Brexit would do well to study how he operates.

This is an extract taken from our Boris’s Britain publication, to read the full publication click here.