COVID-19 has undoubtedly presented governments with one of their most significant communication challenges in recent history. As WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in February, ‘we’re not just fighting an epidemic; we’re fighting an infodemic’.

As our online information consumption increases and media patterns change, we are witnessing an extraordinary spread of global mis- and disinformation. It makes sense that the majority of conversation is now taking place online. People are using the internet to share information, air their anxieties and fill the void of boredom.

A recent Ofcom study showed that 99% of the UK online population accessed a news story about coronavirus every day, and 24% say they were getting news at least 20 times a day. Global web browsing has increased by 70% through the crisis and social media by 61% over normal usage rates (Kantar). In short, the outbreak is making us spend even more time on the platforms we were already addicted to.

Yet the recent surge of interest in disinformation is not because the concept is novel. Our reliance on digital information, coupled with a wider sense of global uncertainty, has made us more vulnerable to manipulation by information.

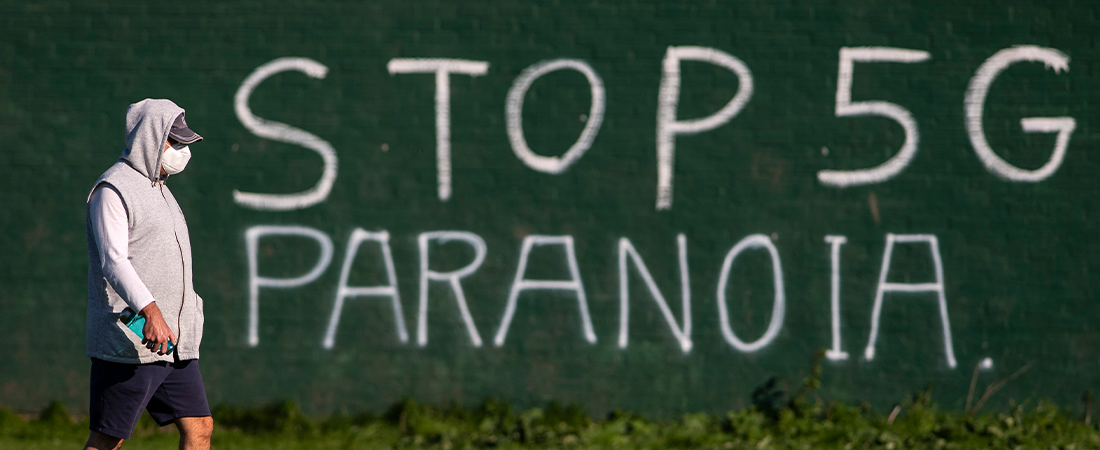

The current climate is a stark reminder of the real-world implications and threat of disinformation. Shocking examples of people drinking chlorine and 5G masts being set on fire have become commonplace news stories.

While governments seek to reassure, we are witnessing a deluge of hostile actors attempting to influence, divide and erode public cohesion. Defined as “the deliberate creation and dissemination of false and/or manipulated information that is intended to deceive and mislead”, disinformation has brought into question the credibility of media outlets, public health organisations and major corporations. Yet what is currently so striking is the unprecedented speed and reach disinformation seems to have.

The concept is so effective because it plays on our cognitive biases. In a crisis fear is rife and people look for simple answers to the complex problems. To gain a sense of security in an unsure world, we look for narratives to confirm what we already think or know. Disinformation often provides this fix.

Since the outbreak and subsequent global spread of the virus, media reports claim that the Chinese government has been quick to take advantage of this. Xi Jinping’s administration has continued to employ the concept of ‘mask diplomacy’. In an attempt to deflect responsibility for the initial outbreak, China has presented itself as the international aid partner of choice – a role the US might have typically held in the past.

Images of Chinese aid being delivered across the world have been widespread. These have included photos of supplies being delivered to the UK, including boxes labelled “Keep Calm and combat Coronavirus” which have, in turn, been promoted to UK audiences by the Xinhua news agency.

Russia also continues to deliver a global information campaign with outlets such as RT maintaining a steady drum beat of messaging. According to the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensics Lab, pro-Russian outlets alleged that US government is behind the virus, a narrative that also appeared on Russian

state TV.

However, if a government attempts to expose and denounce disinformation attacks, they inadvertently spread their messages and tactics more widely. Government communications teams must not treat disinformation like a traditional media story. These activities look to take advantage of an audience using twisted versions of the truth, exploitation of bias and false equivalence.

Government response strategies are dependent on early detection, disruption and long-term defence measures. Robust digital detection programmes are critical for the identification and early warning of emerging threats. However, the monitoring of disinformation is only an initial step. When hostile narratives are persistently supported by software such as bots, governments must have the ability to immediately detect, track and predict the trajectory of information before the threat becomes reality.

‘Off the shelf’ responses to malign information attacks are useless; governments require bespoke strategies which employ a holistic approach to communications. During COVID-19 we have seen governments working with social media platforms with impressive results. Facebook, for example, has taken aggressive steps to stop disinformation, not only by removing up to 76% of potentially harmful content but also heavily investing in over 60 fact-checking partners.

To completely neutralise disinformation is almost impossible, the digital landscape is complex, chaotic, and occasionally narratives can exist without detection. However, to defend against such hostile actions, governments must be in a position to deliver rapid response campaigns which enable

audiences to make informed decisions based on reality and fact, instead of malicious falsehoods.

As governments continue to operate in the midst of an infodemic, they must use this time to acknowledge the reality of the threat that disinformation poses. The challenges which they currently face present an opportunity to invest in their capabilities and develop resilience to future threats.

To learn more about Portland’s Government Advisory practice, please visit https://portland-communications.com/expertise/government-advisory/