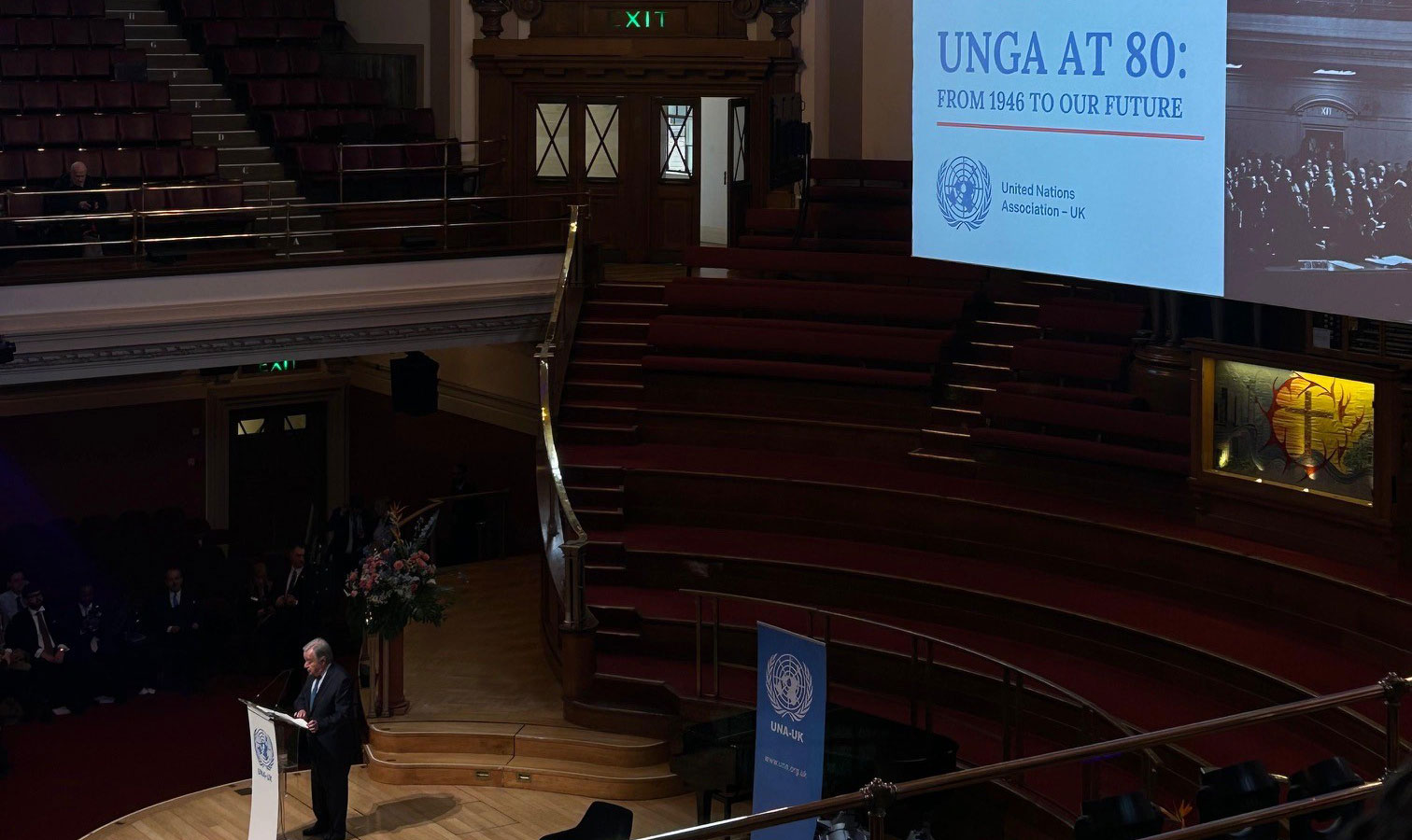

Following the announcement of Trump’s “Board of Peace”, Kaitlyn Radford from Portland’s Healthcare and Life Sciences team – reflects on her key takeaways from UNGA’s 80th anniversary meeting hosted by UNA-UK at Central Hall Westminster in January 2026, and what it signals for organisations working across global health and international development sectors.

Multilateralism is under strain, but it remains indispensable

Eighty years after the first United Nation General Assembly (UNGA), multilateralism is again being asked whether it can deliver in a world shaped by faster shocks, harder geopolitics and deeper distrust. The meeting line-up reflected the scale of that question, with opening speeches from UN Secretary-General António Guterres, UN General Assembly President Annalena Baerbock, and UK Attorney General Lord Hermer, followed by expert panels on topics central to evolving reforms, from peace, security and justice to global challenges such as climate change and pandemic threats.

The key takeaway was that the reform argument is increasingly a “back to basics” case. In a more contested governance landscape – where power is shifting away from traditional institutions and towards informal coalitions and bilateral deals – the UN’s credibility will depend on doing fewer things better, and on showing clearer proof of delivery on cross-border risks that no country can manage alone. That, speakers argued, requires a more streamlined UN focused on its unique mandate and comparative advantage: peacebuilding and international security, upholding international law, and advancing justice and equality. As Lord Hermer simply put it: reforms should aim to restore the UN as the primary convenor and global mediator that prevents crises before they erupt.

Disease threats, climate shocks, and women’s rights are security issues.

A clear theme was that “security” is no longer confined to traditional defence. Climate shocks and health threats were repeatedly framed as cross-border security risks, strengthening the case for renewed cooperation rooted in preparedness, resilience and stronger early warning systems.

Panellists stressed the importance of treating international security investment as distinct from domestic defence spending, while recognising both as essential. Measures such as pandemic preparedness and climate resilience were positioned as frontline components of national defence, reinforcing the need for clearer, more stable budgets that sustain prevention over time. This framing can help reposition prevention as protection – of lives, livelihoods and wider the economy -rather than a discretionary spend.

Speakers also linked legitimacy and outcomes to who is at the table. Women are well known to be disproportionately affected by crisis, and new evidence cited shows that their participation in peace and security agreements can therefore increase durability and the likelihood of success by around 35%. This reinforced calls to embed more women and people with lived experience into advisory boards and coalitions, ensuring representation is built into decision-making as a form of risk management rather than treated as an add-on.

Stronger, more inclusive teams and coalitions reduce global risk

Speakers argued that building the strongest possible teams – regardless of gender, disability age or economic status – strengthens our ability to respond to major global challenges, from nuclear risk, and biological health threat to climate change and food insecurity. They also noted that organisations that treat people differently ultimately undermine their own credibility, weakening trust in the system overall.

This point felt especially pointed given the wider governance backdrop. President Trump’s newly announced “Board of Peace” has been widely discussed as a potential rival forum for conflict management, with critics questioning its relationship to established international law. Meanwhile, in global health, the US has now completed its withdrawal from the World Health Organization, raising immediate questions about continuity in disease surveillance, coordination and funding. In this new world, inclusive coalitions – and trusted institutions that can convene them – become even more central to managing shared risks.

Credibility now depends on accountability as well as financing

Alongside calls to defend multilateralism, speakers stressed the need to demonstrate delivery. With only around one-third of SDG targets currently on track, development is increasingly being pulled towards accountability – not punitive oversight, but clearer answers to the questions the public, partners and policymakers now ask instinctively: what will change, by when, who owns delivery, and what evidence will show progress? Legitimacy will increasingly be won through transparent milestones, measurable outcomes and grounded proof points, not simply commitments.

Another recurring thread was the financial architecture that determines whether countries most exposed to shocks can invest in resilience – or are pushed deeper into debt. This is one reason the UN tax convention process surfaced as part of a broader push for fairer global rules and more sustainable financing, particularly as AI accelerates and wealth inequality risks widen.

Reform is a shared responsibility

As António Guterres enters his final year as UN Secretary-General, he signalled a strong commitment to bold reform, underlining the importance of the UN – and UNGA in particular – as the central forum for addressing shared global challenges.

Yet, the event also made clear that renewal cannot rest with the institution alone. Meaningful reform will require collective political will and sustained engagement on cross-border threats beyond governments. For organisations working across health and development, the wider lesson is a return to fundamentals: fewer promises, more proof. Influence will increasingly be earned through delivery – demonstrating what works, who benefits, and how partnerships translate into measurable, trusted resilience.

If you would like to explore these insights further and discuss what they could mean for you and your organisation, please don’t hesitate to get in touch:

Kaitlyn Radford, Senior Account Manager, Healthcare and Life Sciences: [email protected]

Daisy Thomas, Senior Partner, Head of Healthcare and Life Sciences: [email protected]