It is an interesting time for UK-China relations.

During the summer leadership campaign, Rishi Sunak took a tough approach on China, labelling the country and its governing Communist Party as “the largest threat to Britain and the world’s security and prosperity this century”. He also promised to examine whether to prevent Chinese acquisitions of key British assets and assess Chinese operations in the UK.

The approach to China was one of the agenda items for Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s first call with US President Joe Biden. It is clear that China relations remain at the very top of western foreign policy agendas.

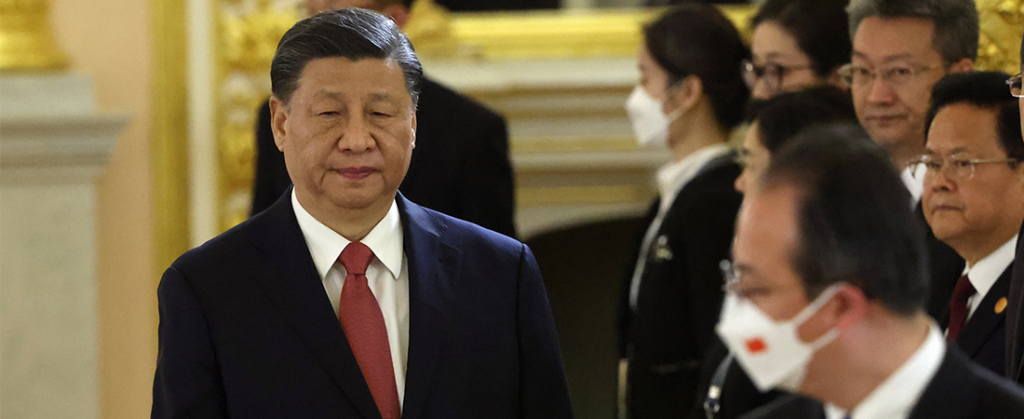

The 20th Chinese Communist Party Congress recently came to a close. It saw President Xi Jinping re-selected as leader, with many believing he has power not seen since the times of Mao. The leadership indicated that it will not yet abandon its zero-covid policy which continues to put cities across the country under restrictive lockdowns. This feeds into a wider picture of China’s economic shift from the ‘factory of the world’ to a more mature service economy. This is not without its challenges, particularly as more countries around the world take a much more hawkish view towards China.

Long gone are the days of David Cameron’s administration and its warm approach to China, remembered for a visit he made with President Xi to a pub near Chequers. Despite Boris Johnson’s approach to be somewhat open to China in line with his ‘global Britain’ vision, he still banned equipment purchases from Huawei on espionage concerns, following significant pressure from the American government. The worsening of relations culminated in Liz Truss’s very hawkish approach. Before she stepped down, it was reported that in the Integrated Review she had planned to formally designate China, not as a ‘strategic competitor’, but as a ‘threat’ to the UK for the first time ever, signalling a major shift in the UK’s diplomatic stance. Further legislation will be interpreted through the lens of this shift. For example, privacy concerns regarding Chinese-owned businesses continue to raise questions, and will look to be amended in the upcoming Data Bill.

The Labour Party’s view on China has also pivoted over recent years. The softening of UK-China relations originally grew under the last Labour government, with Gordon Brown signing bilateral agreements for increased Chinese investment in the UK. Various ministers even attended the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing. Despite this, Labour now shares the Conservative Party’s reservations on China, a position that is often credited to former Shadow Foreign Secretary Lisa Nandy.

The tough stance by recent Conservative governments on China may be in tension with Sunak’s innate economic pragmatism, which could lead him to want to harness more benign relations. Last year, Sunak said that he supports closer economic ties with China, arguing that the UK should look to foster a ‘mature and balanced relationship with China’. While some experts believe that Sunak may adopt a more pragmatic stance and prefer cooperation with China rather than confrontation, others believe his need to keep the party cohesive will result in his government taking a more hawkish position.

Sunak also faces a serious in-tray of domestic issues. Uniting the Conservative Party, the cost-of-living crisis, Russia, among many other things may lead his attention away from China. However, increasingly negative media rhetoric on China, combined with China hawks in the Conservative Party, may bring him closer to taking a firmer approach. Recent high-profile events that have increased this tension include the incident which saw a Hong Kong protestor assaulted on the grounds of the Chinese consulate in Manchester. This incident resulted in widespread calls from MPs to take action against the perpetrators. Prominent China sceptic Iain Duncan Smith tabled an Urgent Question regarding the incident, urging the Foreign Office to declare the Consul-General and any consulate officials involved “persona non grata”. Meanwhile, the story that the Ministry of Defence reported that UK pilots helped the Chinese military was picked up by many national publications, further fuelling nationwide China scepticism.

Plans are already underway to ban China’s Confucius Institutes at British Universities, in line with the pledge Sunak made during the summer leadership campaign, as the sizable contingent of China hawks in Parliament will look to ensure Sunak sticks to his campaign promises. The elevation of Tom Tugendhat, Dehenna Davison, and Nusrat Ghani to Government roles also serves as a sign of Sunak’s seriousness on the issue.

Will Sunak draw a line between party election campaign language and government policy? China scepticism goes down well with Conservative voters, and with parts of the party, but cooperation with China is a necessity in the current bleak economic climate, as well as for addressing key priorities such as climate change. China would be likely to retaliate to a significant pivot of policy, and in the short term, could cause further issues for UK businesses operating in China, or take an approach that negatively affects UK exports to China, particularly in relation to the higher education sector which is a significant export earner for the UK.

Like all things with Sunak’s leadership, his action on China will require a high-wire balancing act. He needs to ensure that the UK is positioned for growth and can benefit from trade relations, meanwhile, his party’s view on China has hardened considerably since 2015 as China’s actions have become a genuine cause of concern. It will be intriguing to watch whether Sunak will follow Truss’s tough style and rhetoric, or whether the economic reality will mean that the rhetoric will stay strong, but the actions will not follow.