The former secretary of state for work and pensions pens his thoughts on Brexit and immigration in this short policy paper.

Summary

The central objective should be to ensure control over the movement of people.

Using a combination of work permits and a cap we would look to control access to work and rights to settlement. Free movement for EU citizens for other purposes should be preserved.

This paper sets out proposals to revise the immigration system, however, also in the annexe it makes the point that more information is required to fully understand the nature of where the cost fall and benefits exist.

The information on much, if not all, of this is held by the government.

Introduction

The recent referendum vote gave government a clear mandate to leave the EU.

What was also clear from the vote was that HMG will, once we have left, need to put in place controls on immigration for EU citizens as well as non-EU citizens.

This paper explores a way to reduce migration pressures on jobs and wages whilst at the same time reducing the pace of population growth to sustainable levels.

It sets out key objectives and indicates some possible variations.

Key Objectives

The following should be the key objectives:

- The rights of those EU citizens who were in the UK on referendum day should be preserved from the outset of the negotiations. They should not form a part of any larger negotiations (this we believe should be reciprocated in respect of British citizens in the EU).

- EU nationals wishing to come to the UK for work should be brought within the present UK work permit system. The level of the cap on work permits should be a matter for a new government to decide, while Intra Company Transfers (ICTs) would be unrestricted unless they became open to abuse. For presentational reasons, a re-launch and re-naming of the system might be necessary.

- Free movement for EU tourists, students and the self-sufficient (eg: many pensioners) should continue in both directions as they are not competing for work, and have little impact on the permanent population. There should be no restrictions on genuine marriage (although robust checks should be in place).

- The large number of EU citizens who have previously lived or worked in the UK at some time but have since left must be subject to these new requirements if they wish to return to the UK to work.

- People should be expected to have secure employment to go to before entering the country.

- People allowed into the UK for work should have no access to income or housing benefits for five years, as it is not appropriate to subsidise labour from abroad while there are unemployed or under-utilised among the existing population, (an alternative could be to require a 4 year record of NI contributions).

Supporting mechanisms

The new system will need to be flexible and should allow the government from time to time to exempt some occupations from any restrictions, whilst tightening up on other occupations to cater for changing circumstances and the economic cycle.

The Migration Advisory Committee’s shortage occupation list could be used for this purpose. For example, scientists might be exempted but a range of lower skilled work would be restricted by both the cap and the permit system.

Where the issue of a permit is being considered, the DWP regional Job Centres should be involved to check whether there is actually a shortage of UK labour in that category and location before issuing permits to business.

It should be possible to leverage information gathered from implementation of Universal Job Match and the new (Universal Credit) Work Coach programme and in-work conditionality to provide new and much better data-driven insights into the potential supply of labour already available.

Some enhancement of the National Insurance number system could be required to distinguish between those granted to immigrants for work and for other purposes, and possibly to allow a time limit to be set on their validity so that they would lapse on expiry of the work permit and guard against ‘disappearance’.

Possible variations

It would also be possible to introduce a Seasonal Agricultural Workers Scheme (SAWS) for EU citizens, provided that it was for truly seasonal work in defined sectors and was limited to six months. Such a scheme was run successfully for many years. It was brought to an end when the UK borders were opened to unskilled workers from Eastern Europe.

There should be no legal or treaty objections to arrangements of the kind outlined above as the UK would no longer be subject to the Lisbon treaty.

Other EU Nations

As regards negotiability, it is worth noting that the larger member states Germany, France and Italy and the rich Benelux and Scandinavian countries do not particularly benefit from mass access to the UK labour market.

To the extent that it is in their interests for their own highly skilled nationals to work in Britain, they would be accommodated under the expanded work permit scheme. These key governments should therefore have no reason, in terms of national interest, to object to a solution of the kind outlined above.

While there have been large movements of people from Eastern Europe it is not at all clear that it is in the interests of the member states in question that this should continue, bearing in mind EUROSTAT forecasts of declining population and worsening demographics, combined with pressure on their own borders from further east (Ukraine, Albania et al).

Their primary interest might be in securing the rights of those already in the UK. This is why an early statement concerning the right of EU nationals already residing here is important.

It should be understood that while controls of the kind listed above can make a real difference to levels of migration, the ‘price to be paid’ if others sought to impose a countervailing restriction on access to the single market should not actually be a high one in purely economic terms.

By way of illustration, if entry to the UK of one of their nationals was ‘worth’ £1,000 to the other member states then measures that cut their numbers by 100,000 a year would represent a ‘cost’ to other member states of £100m a year. In the context of the single market even a multiple of this amount is not a very large sum.

It would also be very helpful – indeed necessary – for officials to make a proper calculation of the actual fiscal contribution of EU migrants in the UK and the potential impact of restrictions on free movement – something that they seem to have been completely averse to doing, either to inform Ministers for the renegotiation or during the referendum campaign.

Migration Watch have estimated that this set of proposals would reduce migration by at least 100,000 per year. Their recent assessment of net benefits and disbenefits from new figures shows that the influx of cheap labour did not benefit the UK as has been supposed. (This is explained in Annex A).

Annex A

(Based on latest HMRC data and Migration Watch assessments)

Background

HMRC and the Treasury have, in general, been reluctant to provide any information of either the costs or contributions of migrants to the UK fiscal balance.

As Secretary of State, I often found the rather weak reason given was that the information was held in different departments and this made it too costly and complicated to compile.

However HMRC finally released in August 2016 a new publication with statistics on receipts of income tax and NICs and payments of tax credits and child benefit to EEA nationals in the tax year 2013/14.

Tax receipts from EEA nationals

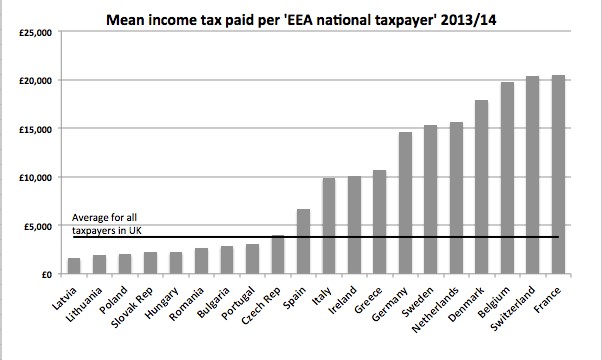

Interestingly, as Migration Watch show, while taxpayers from Western Europe pay on average twice the amount of income tax as the average for the whole UK taxpayer population, taxpayers from Eastern Europe pay only half the average for the whole UK taxpayer.

I believe this information helps show that whilst the arrival of cheap labour from Eastern Europe may have helped some companies in the UK, its overall effect was far from beneficial to the UK as a whole. This makes the argument for Work Permit controls all the more important.

Working-age benefit payments to EEA nationals

The new information from HMRC can be put together with data from the DWP to give, for the first time, a fairly complete picture of working-age benefit expenditure on EEA nationals. This amounted to over £4bn in 2013/14.

| Description | Amount (£m) | Department | |

| In work | Tax credits | 1,549 | HMRC |

| Housing benefit | 724 | DWP | |

| Out of work | Tax credits | 315 | HMRC |

| HB, JSA, ESA etc. | 842 | DWP | |

| n/a | Child Benefit | 714 | HMRC |

| Total working age benefits | 4,144 | ||

Overall effect

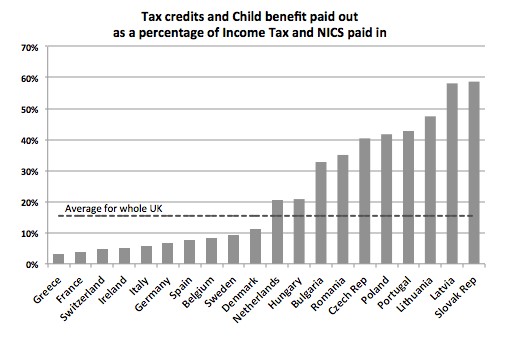

The DWP data is not broken down by country, but comparing just HMRC benefits with payments made to HMRC, the stark divergence between migrants from Western and Eastern Europe can be seen, with nearly half the personal taxes paid by Eastern Europeans going straight back in tax credits and child benefit.

If the DWP benefits follow a similar distribution, then almost all of these taxes go straight back in working-age benefits.

What more should be done

In terms of a properly informed negotiation, it should be obvious that such information and analysis is invaluable in understanding

- Where the relative costs and benefits lie

- How these vary by country of origin

- The likely impact of varying salary levels for work permits

- Consequently, how this might affect Member States differently

Clearly HMRC and DWP have extensive administrative data that can enable a comprehensive picture to be drawn.

This would go beyond the information published so far, firstly to use more recent information that should now be available and secondly to look at matters such as income distribution, regional variations, and nature of employment.

Finally, the HMRC data has again raised questions about just how many EEA nationals are in the UK. This is a matter which the Office for National Statistics has begun to address and again this is important work which should be seen as a priority.