James Ashton, adviser to Portland, asks whether the Chancellor’s review of UK listing rules could ensure more of our best tech companies stay rooted in the UK’s financial market.

SILICON Roundabout to the Square Mile is no distance at all but their inhabitants have remained worlds apart even as Shoreditch’s start-ups upped sticks for fancier offices in Broadgate and Bank.

One tribe is focused on disruptive, explosive growth while the other trades to the drum beat of meeting short-term earnings targets – or so the stereotypes go.

What is bringing founders and financiers closer together now is the maturation of many of the technology ventures nurtured here in the last decade and the hunger to reassert the UK’s place in the world. Why else would one of the first post-Brexit moves made by the Chancellor Rishi Sunak be to review stock market listings rules?

Political shenanigans have not stopped the UK converting a crop of brilliant ideas into category-killing businesses. Excitement about transforming education, healthcare and financial markets attracted a record $15bn investment in domestic tech firms last year, more than the rest of Europe combined, according to Dealroom data. Even a shortage of engineering talent has not stymied progress.

The missing piece is keeping these new-wave titans British – a quaint concept when they could cross borders as easily as the frictionless transactions they administer.

But opening wider the London stock market to tech firms anchors them here, as well as letting others share the wealth they create. Entrepreneurs might sell some shares, not sell out completely, a fate suffered by many promising UK companies before they have reached their potential. Yet to the average freewheeling founder, going public is less pinstripe suit, more straitjacket.

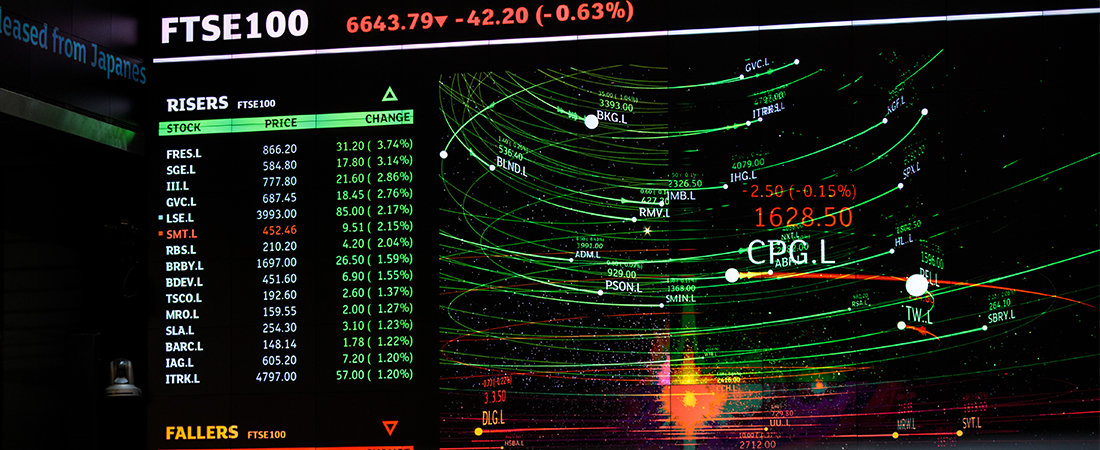

The London market, notably the FTSE100, could do with some digital sparkle. The preponderance of financial and resources stocks contributed to its socking underperformance last year compared with the tech-heavy Wall Street.

The question is one of control. In the quest for better investment growth opportunities, how much should the City bend its governance strictures in order to usher in stocks that might otherwise head Stateside? And how much ground, if any, might tech founders be expected to cede?

Or as Lord Hill put it in a call for evidence for the review he is leading: “The question for us here is whether, consistent with global standards, we can improve the flexibility and proportionality of our regulatory system so as to support growth and innovation.”

London’s public markets are not, as some would have it, a tech desert. For example Asos and Boohoo, recently busy sweeping up old bricks and mortar retail brands, have transformed clothes shopping as well as the portfolios of investors who bought in when they were tiny. A more recent addition, vitamins seller The Hut Group (THG), has posted 50% gains since floating last September.

One niggle is that none of this trio have a premium, main market listing to take them into the FTSE100 and the tracker funds that fill many pensions. The requirement for a 25% free float of shares and a dislike of dual-class ownership structures has kept some founder-led stocks on the fringes of the action, or else retained in private hands. The London Stock Exchange’s main market may have a capitalisation of close to £3 trillion and unrivalled liquidity in Europe, but its participants deserve better.

Those that fear a race to the bottom for standards and who would preserve the FTSE100’s prestige at all costs would do well to remember abject failures such as the recent disintegration of Gulf hospitals group NMC Health. There are others that did not belong there that seemingly passed muster.

And think on how many great investments have been built around one man or woman. How much would Tesla be worth without Elon Musk right now? Investors would not like to find out.

Founders might consider whether ceding more voting rights and appointing some truly independent directors when they go public is really a brake on progress.

I suspect the Treasury will be reluctant to tinker with the sanctity of the premium listing, enticing tech stocks with the promise of lighter-touch flotations but barring them from the hallowed FTSE blue-chip club without significant concessions. It would be a shame if a compromise could not be reached.

Those that talk of Big Bang 2.0 should leaf through the history books. The first Big Bang in 1986 was the answer to an Office of Fair Trading probe, rather than a bold vision of the future. The scrapping of fixed minimum commissions on share trading was the first shoe to drop, leading to the foreign takeover of smaller firms that could not survive on smaller fees, electronic trading and so on.

There is no reason that what started with a review of listings rules could not broaden to create a modern market renowned for transparency and ease of use that puts retail investors on a par with the biggest investment funds. While Sunak is at it – and if he is so keen on revamping the public markets for the benefit of all – he might overhaul a tax system which favours raising debt over equity.

Saul Klein on why tech is not just for techies

Tech jobs are some of the most lucrative in the employment market, but there’s a perception that they’re only for the extremely tech-literate. In this episode, Saul Klein dispels that myth. A technology investor at venture capitalist firm LocalGlobe, Klein has backed a slew of British start-up successes, including LoveFilm, Improbable, TransferWise and Kazoo. In conversation with episode host James Ashton – a Financial Journalist and Senior Adviser at Portland – Klein also discusses how the UK can stay on top of Europe’s tech industry, the “New Palo Alto”, and how a £50 billion valuation has become the new £100 million valuation.

Listen on: Apple Podcasts, Spotify and Google Podcasts.