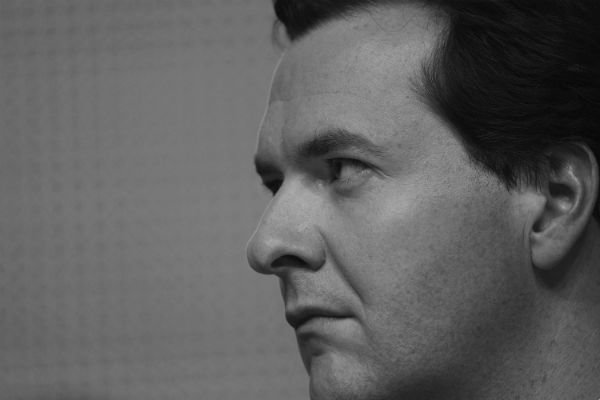

George Osborne’s last budget speech may be the one he is remembered for. After the omnishambles of 2012, but much more assured performances since, this is his last chance to make an offer to the electorate.

Recent history shows how the challenge has changed. The Tory governments of the eighties and nineties had a simple strategy for pre-election budgets: put money in people’s pockets. Then sheer parliamentary strength allowed the Blair administration to set its own rules. Mr Osborne can do neither, but can learn from these past budgets.

In 1983, Geoffrey Howe was unable to reform tax as much as the Government wanted, but still found room to cut taxes by £2bn. Following a more radical period, and on the back of Thatcherite economic growth, Nigel Lawson in 1987 managed to cut taxes, increase spending and reduce borrowing. The opposition was left asking what could be done about unemployment, to little effect with the electorate.

Norman Lamont in 1992 was the last Conservative Chancellor able to be generous in his pre-election budget . Facing difficult polling numbers, he went for broke with a tax cut funded by increased borrowing. After returning to government, he was forced to increase taxes substantially as part of a collapse in credibility.

This meant that after a deep recession and the ERM fiasco, Ken Clarke’s budget late in 1996 was left trying to make up ground, promising a ‘Rolls Royce recovery’, while also finding time for some base-pleasing measures like a cut in income tax and an increase in the married couple’s allowance.

The judgement on that government’s economic competence was though already in, so that by 2001, Labour was able to set the pace entirely, outlining spending increases on health and education and daring the Conservatives to oppose them in favour of lower taxes (at a time when even the Tories promised to grow spending by 2.25% a year).

By 2005, a pre-crash Labour remained supremely confident and Gordon Brown’s budget continued the emphasis on health and education, although he did take cheaper properties out of stamp duty and gave pensioners a council tax rebate.

In 2010, though, Alistair Darling had to present a budget to cope with a calamitous recession, while also trying to find the way towards fiscal credibility after an expensive spending streak.

He did what he could with a very limited hand, cutting stamp duty for first time buyers and raising the winter fuel allowance. He also tried to present a picture of economic competence, cautiously pointing towards reduced and falling deficits. But by this stage Mr Darling’s efforts were doomed.

Mr Osborne will be aware of all this history. The ‘bribes budget’ is no longer an option. Instead, the new rules are: establish competence, focus tax cuts on the worst off, help home owners and make sure pensioners feel good. Expect this to be the pattern tomorrow.